Seeking paydirt

It’s a gamble, of course, like any investment, but mineral exploration has the potential for wildest-dreams-style payouts

Eagle Plains Resources Ltd., a Cranbrook, B.C.-based mineral exploration company, was founded in 1992 by Bob Termuende and his son, Tim. — Photo courtesy Eagle Plains Resources Ltd.

Mineral exploration is a long-shot game with a high expectation of failure—so what attracts people to it? We talked about that and other aspects of the industry with Tim Termuende, CEO of Eagle Plains Resources Ltd., a Cranbrook-based junior exploration company that is celebrating its 25th anniversary in 2017.

Termuende is a professional geologist who co-founded Eagle Plains with his father, Bob, in 1992, and has been the CEO since Termuende senior retired in 1999.

Please explain what a junior mineral exploration company is and how it works.

A junior mining company relies on investors to provide money for exploration—that’s basically what separates us from major mining companies. We’re doing exploration rather than actually digging up a product. Some majors also explore, but they are self-financing, using revenues from existing mines to generate new discoveries.

The high expectation of failure and the realization that the deck is stacked against us are what compelled us to evolve into a prospect generator. We do a lot of research and acquisition of projects at very basic costs and we bring in partners to spend the bigger, higher-risk money.

The company’s financial support can come from its shareholders in the form of private placements, or from partners who have their shareholders buy into the company. We take the early risk, doing initial fieldwork, testing ideas and concepts. When we find a project that looks promising, we can sell an interest in it to other companies who are interested in the potential gains down the road.

Tim Termuende heads up Eagle Plains Resources Ltd., a project generator in junior mineral exploration. — Photo courtesy Eagle Plains Resources Ltd.

And what are the odds of striking it rich?

Statistically, you’ve got to spend roughly $100 million to find a significant ore deposit. It’s a bleak reality of this business. You expect to get disappointed a lot, and you get used to it, but you still have to have the dream (and the belief) of making a big discovery. The odds of making a mine from a single mineral occurrence are roughly one in a thousand—we joke that “you have to kiss a lot of frogs.” But if you spend $100 million, on average, and you find a deposit like the Sullivan, that’s worth $40 billion … it really is worth doing the exploration.

How do you decide where to look?

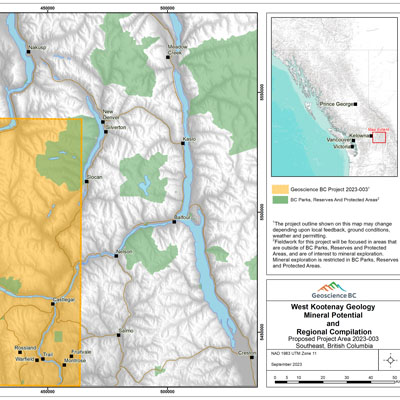

Mines are huge economic generators that provide thousands of jobs and countless other economic benefits. The provincial government recognizes this and conducts geoscience work all over British Columbia to stimulate exploration. They’ll do airborne geophysical surveys, regional geological mapping and Regional Geochemical Surveys (sampling that analyzes the fine gravels of creeks in an area). Every six months to a year they’ll publicize the results, and prospectors and companies like ours are watching all the time—it’s like Christmas morning when they put out these results.

How did you get introduced to the industry?

I was a bush-rat when I was a kid and always had a passion for rocks. My dad is a geologist too, so I tagged along into the field with him all the time. I think I was five years old the first time I went out to northern Saskatchewan with him, and often I would visit him on sites where he was working.

Tim's son, Eric Termuende, spent a few summers working with him at remote mineral exploration sites before pursuing a degree in business. — Photo courtesy Eagle Plains Resources Ltd.

I was 12 the first summer I joined up with a crew in the bush by myself, and I did that every summer after that. I was always the youngest guy on the crew and I learned from the ground up. I was a sponge, doing camp chores like cutting firewood, and asking a lot of questions. I eventually got a degree in geology from UBC in the mid-'80s but I think I was always destined to be a rockhound, and always held a burning desire to make a major mineral discovery that eventually became a mine.

In 25 years, what’s been your biggest find?

In 2007 we had a project called Copper Canyon, north of Terrace, B.C., that turned into a pretty big deal. It was a known discovery when we acquired it in 2001 (for about $10,000), but very underexplored. After attracting a partner, the project developed into a big gold and copper resource—a couple million ounces of gold and over a billion pounds of copper. We separated that project into another company called Copper Canyon Resources, and in 2011 the company got taken over for $65 million. All the original Eagle Plains shareholders had a big payday.

Bob and Tim Termuende (second and fourth from left) with their crew at the lucrative Copper Canyon project. — Photo courtesy Eagle Plains Resources Ltd.

We hope to do it again. We’d love to be in a position where one of our projects—ideally a local project here in the Kootenays—showed great promise, and we could spin that project out the same way and then sell it to a major company.

There have to be some rewards in the meantime, though, right?

Between Eagle Plains and our subsidiary TerraLogic Exploration Inc., we’ve grown to having 15 full-time, well-paid employees—about half of them are geologists—so we’re a significant employer providing good, stable jobs. It’s not uncommon to have our ranks swell to 40 or 50 people during the busy exploration season. We’re happy and proud of the fact that even during the tough periods we have been able to keep everyone who wants to be around.

Over the years Eagle Plains and its partners have invested a minimum of $20 million into the East Kootenay and over $50 million into Western Canada. A lot of money comes into the Kootenays for our projects, and that’s a big benefit to the area. With tenacity, perseverance and a little luck, we are hopeful we will make a big strike in the area.

Tim Termuende (far right) shares a light-hearted moment with some of the crew from Eagle Plains Resources — Photo courtesy Eagle Plains Resources Ltd.

Comments