“A book of hope:” Ktunaxa Nation shares the story of its land and people

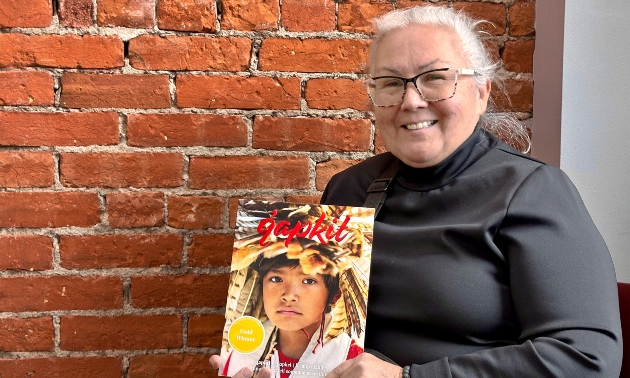

KootenayBiz had the honour of chatting with Lillian Rose on the origins of Q̓apkiǂ—a book that celebrates Ktunaxa culture

— Kerry Shellborn photo

“Who are the Ktunaxa?” shouldn’t be a question that Kootenay residents have to ask. After all, archaeological evidence shows the Ktunaxa have lived in the region for thousands of years.

Even though I grew up in the traditional lands of the Ktunaxa and now reside in Cranbrook, it is a question I have often asked myself. And I don’t think I’m alone.

I had the privilege of meeting Lillian Rose to discuss the creation of Q̓apkiǂ, a book that beautifully honours Ktunaxa culture, stories, history, and art. Q̓apkiǂ means “to tell someone everything” in Ktunaxa.

I met Rose on a cold November morning while the first snowflakes of the winter season began to fall outside the the Ktunaxa Nation government building in Cranbrook. Although it was cold outside, Rose’s smile was warm as she shared her story.

Rose is Traditional Knowledge and Language Coordinator at Ktunaxa Nation Council. A silviculturist by trade, Rose’s heart belongs to basket weaving, which she considers her dream job. Her eyes dance with joy as she regales me with stories of her youth, wandering through the land in search of perfect plant specimens to create traditional Ktunaxa baskets. Today, Rose generously shares her craft with the next generation, holding workshops in her ʔAkisq̓nuk (Windermere) hometown, where she passes down the art of basket weaving along with the cultural traditions woven into each piece.

When asked about her new passion, q̓apkiǂ, a book about her people, she said “the demand for our elders, speakers and knowledge holders’ [time] is incredible.”

Ktunaxa culture is very person-centred with oral, not written traditions. The release of this and other publications has been changing that over the years.

Rose told me that another reason for the book is that the Ktunaxa Nation would love to have it used in the British Columbia school system. When I first heard that I thought that the book might be structured like a text book, but that couldn’t have been further from the truth.

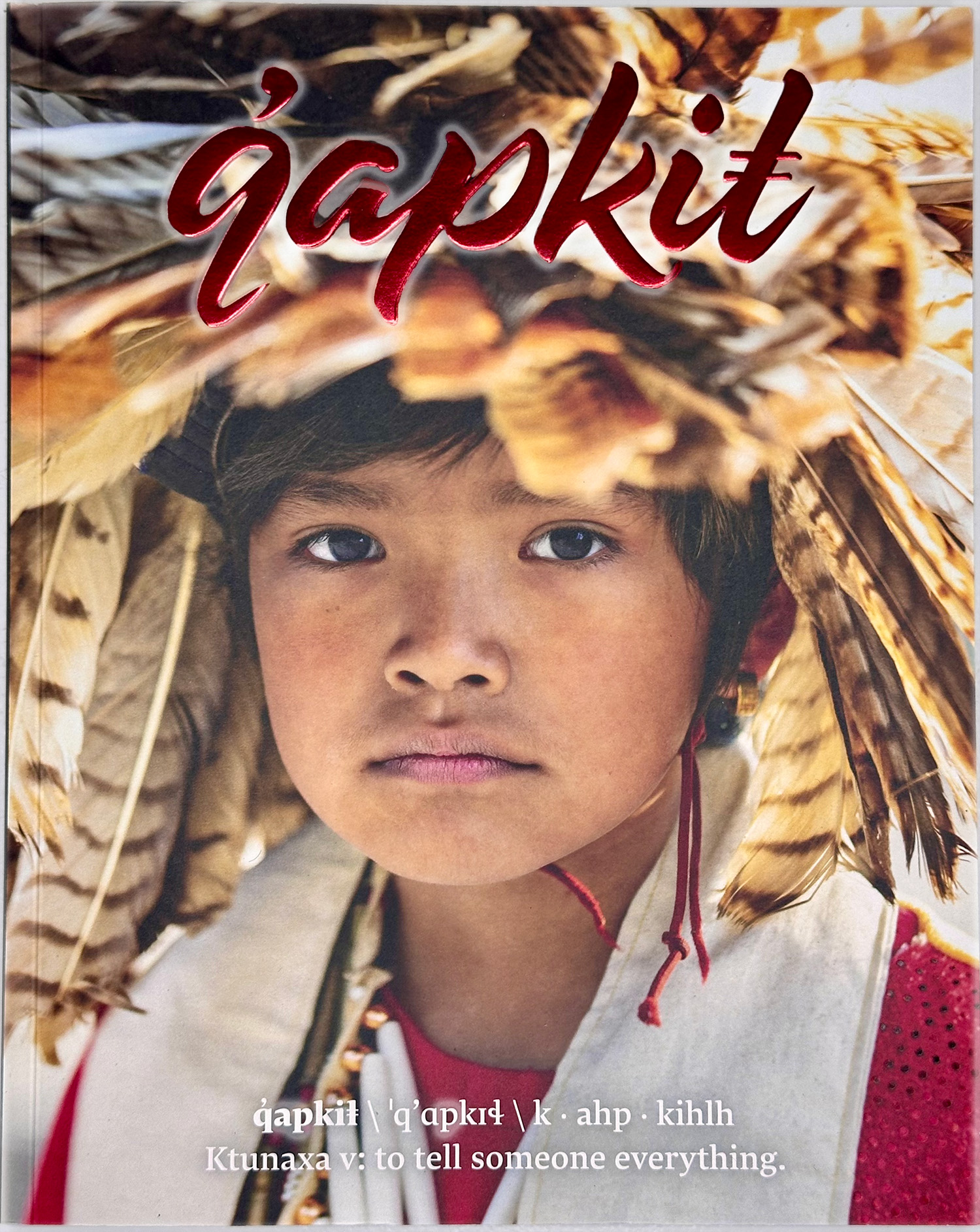

Q̓apkiǂ is a visually stunning work that feels more like a cherished coffee table book than a traditional textbook, thanks in large part to the high-quality paper carefully chosen by the Ktunaxa Nation Traditional Knowledge and Language Advisory Committee, who were involved throughout the process. Local photographer Nicole Leclair spent a year traveling to Ktunaxa festivals, capturing people in their environments, while writer Martina Escutin (Shovar) visited villages and homes, gathering heartfelt stories that bring the spirit of the Ktunaxa people to life.

Q̓apkiǂ is a visually stunning work that feels more like a cherished coffee table book than a traditional textbook, thanks in large part to the high-quality paper carefully chosen by the Ktunaxa Nation Traditional Knowledge and Language Advisory Committee, who were involved throughout the process. Local photographer Nicole Leclair spent a year traveling to Ktunaxa festivals, capturing people in their environments, while writer Martina Escutin (Shovar) visited villages and homes, gathering heartfelt stories that bring the spirit of the Ktunaxa people to life.

The book is filled with personal stories like the one from Troy Sebastian, whose family often went on long summer road trips. He vividly remembers the first time their family entered Kootenay National Park where he relates:

“As we approached the park entry gate, I could feel Dad’s tension rise and my mom’s concern was clear. This is where park visitors are required to pay for a park pass. The staff asked us to pay for a pass. My dad refused. He said, “This is our land. Why should we pay for a park pass? You should pay us.””

Not many school textbooks have gems like that in their pages.

Rose’s vision has come to fruition but her work continues. She is now on a publicity tour with stacks of books in her white van and personally sharing the knowledge of the people and land of the Ktunaxa Nation.

Here is a condensed version of the interview I had with Lillian Rose as she shared her personal story of how Q̓apkiǂ went from a seed of idea to completion.

Okay, so let's start with who you are and how you describe yourself.

My name is Lillian Rose. I'm ʔakisq̓nuk, and I work for the Ktunaxa Nation Council in the traditional knowledge and language sector as the coordinator. One of my roles is to incorporate Ktunaxa knowledge at all levels of the organization and share it with the general public.

Among other things, I’m also a basket maker. I’m very connected to the land and the plants we traditionally use for basket making. That’s my dream job—making baskets.

So you’re a creator?

I am, yes. I’m very creative and have been for a long time. I remember as a child, my dad humouring my artistic antics.

Let’s dive into that. Where did your creativity and upbringing begin?

I was born and raised in ʔakisq̓nuk, Windermere. I lived on the reserve until I turned six, then became a hostage at the St. Eugene’s Mission Residential School. That’s a story in itself. But I remember some nuns there encouraging my artwork. My father was also very supportive and would bring things home for me to create with.

So your art started hands-on?

Very tactile, yes. But I was led to believe you couldn’t be an artist and make a living, so I spent much of my career working for the government and industry in the natural resource sector. That experience connected me deeply to the land. I learned about our territory and cultural practices, like finding plants and materials to perpetuate traditional knowledge.

What influenced your connection to history?

Growing up, I heard stories about our creation and the land—vast water bodies, sea creatures, and river valleys. We’ve been here for 10,000 years, and I wondered how we knew that. Then, through archaeology sites in and around Skookumchuck, where we found artifacts below a 6,800 BC ash layer from Mount Mazama in Oregon. That confirmed our presence here for over 10,000 years, validated by oral history and Western science.

How did your work with silviculture contribute to your knowledge?

In the 1990s, I worked with the Forest Service during a shift in British Columbia's recognition of Indigenous voices. Forestry didn’t just focus on trees; it examined the understory. That’s where I grew interested in plants, travelling across territories and continuing cultural practices.

Let’s talk about the book, Q̓apkiǂ. How did that journey begin?

I noticed a lack of resources about Ktunaxa. It’s still very oral and person-centred, placing immense demand on elders and knowledge holders. Originally, I studied to be a teacher, so curriculum development was familiar to me.

Around 2019, two individuals—one a schoolteacher and the other a Parks employee—embraced truth and reconciliation and sought to amplify the Ktunaxa voice. They introduced me to a federal program, Stories of Canada, which lacked resources for teaching Indigenous studies in schools.

I pitched a vision for Q̓apkiǂ, but then COVID hit, and everything stalled. I was raising my 10-year-old granddaughter and needed a job, so I came out of retirement and applied for the Traditional Knowledge and Language Coordinator position. I was hired and handed in my earlier proposal. It felt meant to be.

Tell me about q̓apkiǂ—what does the title mean?

Q̓apkiǂ means “to tell someone everything” in Ktunaxa. We had another name initially, but it didn’t feel right. After discussions with elders and language speakers, we realized the original name was closer to “gossip,” which felt misleading. We wanted the name to reflect openness and honesty, and Q̓apkiǂ was perfect.

What about the contents?

We knew the public had many questions. We’d been giving tours for years, and we saw patterns in what people wanted to know. We also wanted to balance out the focus on residential schools with the many amazing things happening in our community and the people doing great work. The content includes our creation story, the natural processes of our land, archaeological evidence, and more. It’s also a way to document the struggles we’ve faced, especially protecting our land and resources, such as in the fight for Jumbo (Qat’muk). This publication tells the story of how our land has always been ours, despite what history may say.

How was it received?

It’s been part of the ongoing work to educate people. The book has a timeline of impacts on our territory and is a resource for our speakers. It's something they can use to start conversations. The book is a living document, something that continues the dialogue.

A lot of the pre-work had been done. I had another job related to publication, but I didn’t realize they wanted me to write a book. But I set up the structure, pages, and outlines. It was satisfying to see it come to fruition.

How was the visual design of the book?

I wanted it to be beautiful. We have amazing photographers, and we wanted the photos to reflect the land and the people. We worked with a young photographer who captured the community, the landscapes, and even the residential school history. Nicole, from Marysville, Kimberley, was commissioned to capture the community events. The cover photo was one of the 10,000 images she took that year. Narrowing them down was tough! The book is a starting point for deeper conversations. It’s a resource that people can use to build upon.

How is the book being distributed?

Right now, the Columbia Basin Environmental Education Network is selling it online. For large orders, people can contact me directly. We’re working on expanding distribution, and we’ve partnered with several bookstores and organizations, including the Banff Film and Book Festival. It’s in museums and chambers of commerce around the territory, and we’re aiming for a second wave of marketing.

So, people in the Kootenays can ask local bookstores to carry it, or order it online through Columbia Basin?

Yes, or contact me directly for bulk orders. We offer a discount for orders of 20 books or more.

Comments